"Rumpel" by Jessi Jezewska Stevens

"Over the tops of our monitors, we each confirmed the other was still there."

Once upon a time, over a decade ago, I filled out a March madness bracket on a website that offered Bitcoin prizes. It was the innocuous precursor to today’s sports betting and prediction markets. The site was run by a Bitcoin enthusiast who had currency to spare. It was free to submit a bracket, so—procrastinating on something or other—I did, despite lacking any knowledge of college basketball. A coworker explained “seeds” to me. My methodology was to overly believe in the underdogs. March ended, and my bracket—though far from perfect—was prescient or maybe just random enough to win me a fraction of a Bitcoin. It was a small fraction: maybe 1/4 or 1/6. I don’t actually remember. At the time, a Bitcoin was worth around $100, sometimes less, sometimes more. You probably see where this is going. At first I basked in my minor victory. I put the Bitcoin fraction in whatever eWallet I was instructed to set up. I did not spend it. Once in a while I read, with fascination, that Bitcoins were not only weirdly still a thing, but increasing in value. I know you see where this is going. By the time this imaginary currency had acquired unmistakeable real-life value I had lost track of my eWallet, lost access to my company email address, lost the passcode. (Today a Bitcoin is worth $93,976.05.)

Were Rumpelstiltskin to appear and offer me access to my Bitcoin in exchange for a loved one, I would say: thanks but no thanks. This is what happens in Jessi Jezewska Stevens’s futuristic fairy tale, “Rumpel,” except our protagonist (heartbroken, depressed) has misplaced $230 million when binary-code speaking imp tells him: “I can calculate your password, but in return, you must give me your next girlfriend.” (If it were $230,000,000 at stake I would consider; it would depend on the loved one.) He agrees; he gets his money back. And then, of course, he meets someone.

The story is imaginative, energetic, epic. It’s futuristic and old fashioned, gratifyingly virtual and IRL at the same time; it captures how strange it feels to be alive right now, part creature and part machine, or maybe just part cog. Reading it reminded me of this haunting article. It also reminded me, fondly, of an animated Japanese fairy tale series from my childhood called Grimm’s Fairy Tale Classics (via Nickelodeon).

In “Rumpel,” the populace is addicted to a “terribly beautiful” video game called KINGDOM (not only “the most popular game ever created,” but “the most aesthetically pleasing experience the world has ever had”). Addicts are unable to stop playing: “At the supermarket, I caught a young man frozen before a bin of bananas. He was brushing his teeth, though there was no toothbrush, no toothpaste, no sink.” At first it seemed odd that brushing teeth might be part of a video game, until I realized how true it was: so many video games are about ordinary tasks. There’s a game I play with friends (and truly love) called Overcooked, in which you are a tiny chef preparing and serving food in a busy restaurant. (Sometimes the restaurant is on a hot air balloon and the kitchen catches on fire.) Why are we drawn to labor in games? Why are real-life chores a harder sell? The French onion soup I “cook” and “serve” on Overcooked does not actually feed me. (In fact we have grown very hungry losing hours to Overcooked.) One difference is that in games you can win. As in fairy tales, there can be a happily ever after.

Recently, on an unseasonably warm February day, I was on a hike. The trail hugged a hill that overlooked a freeway (extremely LA). Everything below looked like a model of itself, like SimCity—tiny houses and puffs of treetops, semi-trucks like Pez dispensers. As the sun began to set, the hill I was standing on cast a dramatic shadow, as if to assert it was real. Are we living in a simulation? I wondered, mildly. Then: What would it change if we were? Through our screens we have placed ourselves in something like one. Games, fairy tales, fiction—they’re simulations, too. They mimic our world (not always closely), and let us recoup our Bitcoins. What’s the point? I have no idea. Maybe it’s to learn something, or be changed. Maybe it’s just to enjoy ourselves.

Read “Rumpel” by Jessi Jezewska Stevens at The Baffler (link here). You can also find the story in her story collection, Ghost Pains (2024). Thank you, TJ Heesh, for recommending “Rumpel” and Stevens to me in last week’s comments section!

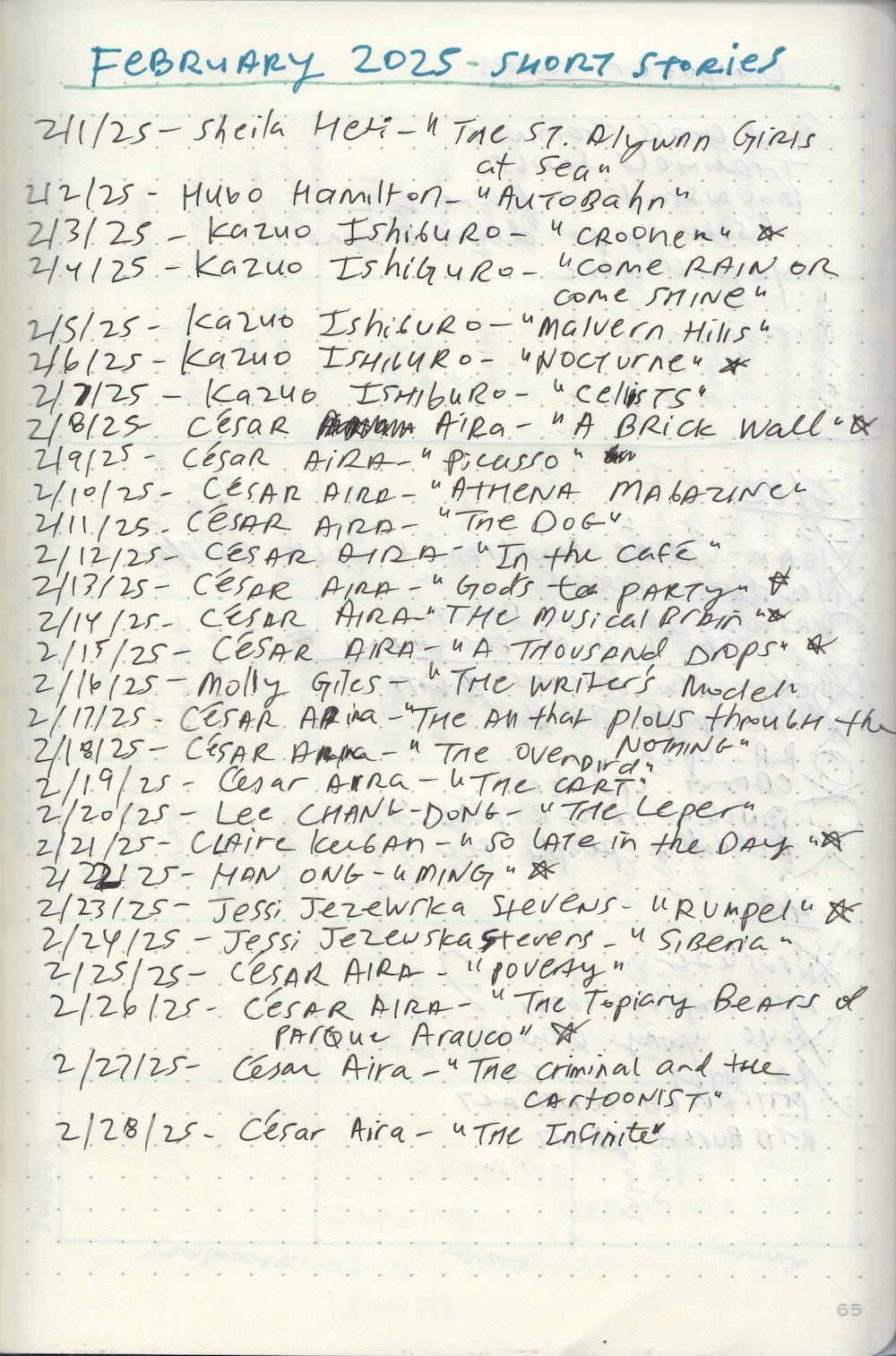

This month I read stories from random New Yorkers, Kazuo Ishiguro’s Nocturnes (2009), and César Aira’s The Musical Brain (2015). Online, I read several stories recommended by SSS readers: “So Late in the Day” by Claire Keegan (thank you, Dinesh!); “Rumpel” and “Siberia” by Jessi Jezewska Stevens (thanks, TJ!)

Tell us what stories you read this month! Any thoughts on “Rumpel”? Any Bitcoin tales? Other story recommendations? I’ll select one commenter to snail-mail a short story to.

In need of a story to read? I’ve compiled a list here.

Hi, Rachel--I read Ghost Pains this summer. While some of the stories seemed unfocused or unfinished, the good stuff is really good: inventive, funny, and unpredictable. I'm eager to see what Stevens writes next.

Also, Han Ong has a story in a recent New Yorker that I just loved; here is a link:

newyorker.com/magazine/2025/01/20/ming-fiction-han-ong

I was reading Kaveh Akbar's Martyr! at the same time, and it was interesting to see how the texts, both about making (art, community, desire) and unmaking (addiction, desire again!) resonated with one another.

And George Saunders just wrapped up a discussion in his Story Club of "The Death of Ivan Ilych"; I hadn't read any Tolstoy since struggling with Anna Karenina in high school, and "Ilyich" is full of wonderful surprises.

aww yay!

this is great : )